Thanks to generous support from the Constance A. Sadler & G. Paul Moates Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs Excellence Fund, we provide funding of up to $2,500 each year for two undergraduate students to conduct human rights-related research with faculty members of their choice.

All Human Rights minors are eligible to apply for this award. The call for proposals is sent out to our students and faculty each spring.

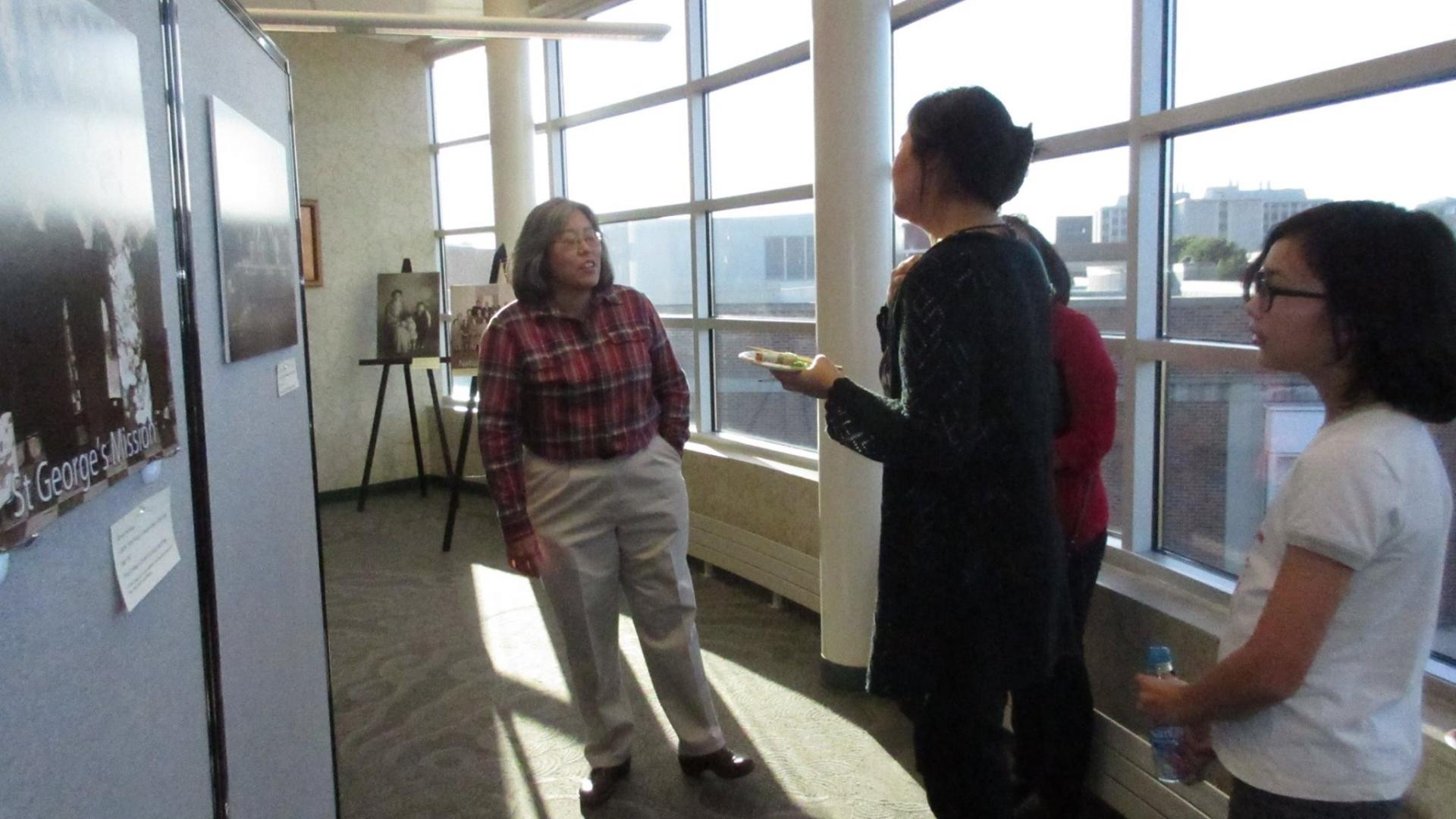

“The grant I received helped fund my research into the Japanese in Nebraska. The project culminated in my publication in the Winter 2015 edition of Nebraska History. It also allowed me to present my research at two events, one held here in Lincoln which was a photography exhibit and lecture and the other at an all day conference that was held in Scottsbluff, Nebraska this past October. There are also two upcoming events where I will be giving presentations including a lecture at Creighton and a talk on how to represent multi-culturalism in Museums in April.”

Griffen Farrar,

who worked with Dr. Parks Coble of the Department of History

“Receiving the undergraduate research fellowship in Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs afforded me the opportunity to have my first formal research experience and learn how to do legal research while working closely with Dr. Courtney Hillebrecht. I assisted Dr. Hillebrecht with her research on international courts, specifically focusing on the International Criminal Court; a large part of my research involved analyzing the situations in the states the Court was examining and investigating at the time. My fellowship not only taught

me a new skill, but it also served as a stepping stone for my senior thesis the following year.”

Sarah O'Neill,

who worked with Dr. Courtney Hillebrecht of the Department of Political Science

"Although solitary confinement is used the world over, American prisons, in particular, seem to demonstrate a certain fondness for the practice. Some estimates have suggested that as many as 61,000 people currently reside in solitary confinement in the United States alone--other estimates have placed the number closer to 100,000. Notably, these estimates often do not include juvenile detention facilities, local and country jails, or immigrant detention centers. For the sake of illustration, consider that even on the lowest credible estimate, there are enough people in solitary confinement in the US to fill Madison Square Garden nearly three times over. These unfortunate individuals spend 22-24 hours per day in total isolation. The cell that serves as their home is often smaller than the average parking stall.

While it is tempting to think of the times when one craves solitude while imagining solitary confinement, it would surely be a mistake to fall for this trap. Solitary confinement is associated with effects that include hallucinations, perceptual distortions, psychosis, diaphoresis, depression, heart palpitations, and insomnia. Clearly, the isolated inmate's alienation is of a distinct nature. Actions that constitute sufficient reason to be placed in solitary confinement include abusive language, failing to stand for count, talking back to a guard, being out of place, being suspected of belonging to a gang, and possessing underwear other than that officially issued by the prison. It is noteworthy that solitary confinement is imposed in a primarily extrajudicial manner; no judge or jury would dream of subjecting someone to solitary confinement for the mere possession of contraband underwear. And yet, it seems that solitary confinement is a practice of dubious moral standing even when used less arbitrarily.

In On Solitary Confinement, I argue that there exists a moral duty not to subject prisoners to unnecessary suffering. In the paper, I provide several routes to establishing that such a duty exists, each of which is mutually compatible and sufficient in itself. I also argue that solitary confinement inflicts unnecessary suffering on prisoners. In order to establish this claim, I seek to show that there is no legitimate aim of solitary confinement that could not be fulfilled in some better way. Each popular justification of solitary confinement withers under careful scrutiny. If it is true that (a) we ought not to subject prisoners to unnecessary suffering, and (b) solitary confinement inflicts unnecessary suffering on prisoners, then it follows that (c) we ought not to subject prisoners to solitary confinement."